Abstract

Partial shading is a common problem that affects bus regulation in DC microgrids with several photovoltaic (PV) modules as energy sources, as a result of reduced solar irradiance reaching the modules. The problem can be mitigated by incorporating batteries, but if they are not included, appropriate control strategies must be used. This paper presents a new approach in a PV-based DC microgrid, which provides a high quality bus voltage regulation in islanding mode, without being affected by partial shading or problems associated with PV module connection and disconnection. The solution proposed herein ensures a proper voltage regulation without being affected by problems such as failures in PV modules or mismatch between them. Besides, it can help to prevent PV partial shade stress by disconnecting the modules affected. A further advantage of the approach is the flexibility to connect more PV modules. The advantages of this approach were verified in a 200 W prototype.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Nowadays, energy requirements have increased worldwide, and the environmental problems associated with energy production by fossil fuel combustion must be solved with eco-friendly generation techniques. Local generation, distribution, and consumption of energy have become a feasible option to satisfy energy requirements in a sustainable manner with expanding residential applications [1].

In this context, the concept of microgrid emerged from the need to incorporate renewable energy sources (RES) into the electric power supply [2]. A DC microgrid can be described as a grid subsystem that allows the interconnection of distributed generators (DG), energy storage elements (ESE), and local loads within a restricted region [3]. A microgrid must provide a secure and economical operation at all time, while simultaneously it provides a high level of reliability in the bus voltage [4]. Two operating modes are possible in a DC microgrid: grid connected mode and islanding mode. The first one is divided into common grid-connected and unidirectional grid-connected. The second one is divided into intentional islanding and unintentional islanding [5].

The advance in solar energy sources has fostered the rapid deployment of photovoltaic (PV) systems. The performance of a PV module in an array connected to a microgrid may be affected by factors such as partial shading, low solar radiation, mismatches conditions, deterioration on PV cells and damage suffered in a single cell [6,7,8]. Some of the aforementioned problems can be alleviated with suitable PV module arrangements. Furthermore, PV series-parallel connections with full-cross-tied or linked bridge may mitigate some factors that degrade the power generation [9,10,11].

Partial shading in PV systems is often inevitable. Shadows of buildings, trees, clouds and dirt can reduce the total output power. Energy losses in the shaded cells can increase, and a major problem occurs when shaded cells get reverse biased [12].

PV module arrays with its own DC-DC converter solve problems associated with partial shading [13,14,15], where the converter topology used is a key element. The converter topology determines the manner in which the PV modules will be connected to the architecture [16, 17].

Several configurations have been proposed to interconnect the converters. Nonetheless, so far three have gained most preference.

The first one is the series input-parallel output (SIPO) connection, which provides high output current [18], and is suitable for applications with low DC voltage.

The second and third ones are the parallel input-series output (PISO) configuration [19], and the distributed input-series output (DISO) configuration [20]. They can provide higher output voltage due to the series output connection. In addition, these configurations provide more efficient energy transfer methods [21].

Although the configurations help to solve the partial shading problem, in terms of power generation, bus voltage regulation issues remain, especially when the microgrid is isolated and has no storage elements.

In order to guarantee bus voltage regulation, two commonly-used methods have been proposed. The first one is the droop control method. This is a simple technique to achieve current sharing. The bus voltage is first measured, and afterwards the amount of energy that each source will supply is calculated [22]. The second method is master-slave control. This technique depends on communication between converters: a master controller regulates the DC voltage and sends the set-points to the other converters [23,24,25], with a very good load sharing ability even if the converters are not identical. However, neither the droop control, which has an inevitable disadvantage of bus voltage deviation, nor a common master-slave control, which requires communication between converters, is able to provide a comprehensive solution to the DC bus regulation together with the partial shading problems or PV module failures with an appropriate control strategy.

This paper presents a DC microgrid with PV modules as RES which can tolerate partial shading problems and the connection/disconnection of PV modules. A new multi-model control strategy approach is used to produce a high quality DC bus voltage to sustain a normal load operation without being affected by the aforementioned problems. The proposed solution is implemented in a digital platform which is used to regulate the dynamic performance of individual units, and to coordinate switching behaviors.

2 DC microgrid architecture

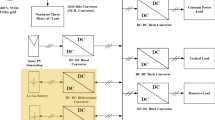

The DC microgrid herein used for the test is shown in Fig. 1, and it consists of a 200 V bus at which DC loads and RES are connected.

The RES are incorporated by a set of 4 rated DC-DC converters of 100 W. The flyback converter is selected, as a link between the PV module and the DC bus, because it provides galvanic isolation, and the ability to connect the converters in a DISO configuration. The entire PV stage consists of 4 Yingli Solar (model YL110WP) PV modules, and it is installed at the Electronics Department of the Technological Institute of Celaya, located at 20°32′15′′N 100°49′00′′W. The DISO configuration, in contrast with conventional structures, allows connecting several RES, brings modular interconnections and offers the possibility to increase the output voltage to high levels increasing overall efficiency, reducing stress in the converters. The isolated converters facilitate the output series interconnection with greater simplicity.

2.1 Partial shading and fault condition

The partial shading effect is a phenomenon that occurs when the solar irradiance levels received by PV cells in a PV module may be different from each other when a portion of the module is in shadow. This phenomenon can damage PV cells since hot-spots can be generated [26]. Therefore, bypass diodes are incorporated to prevent cell damage.

Three conditions are considered for the PV modules used: optimal operation state, partial shading and fault conditions.

In the first instance, no fault is presented, and an optimal state of operation brings a distributed power demand between the modules. In the second one, partial shading can happen individually or in groups. However, each PV source is capable of providing the most possible energy required due to the distributed connection, and because each module has its own converter. In the last one, the PV module is unable to provide power to the microgrid because it does not have the minimum solar radiation needed or it is damaged. In this case, two different operating conditions are considered in which the microgrid may operate.

The first case occurs when one failure in a PV module is presented, where the module does not have the minimum necessary power requirements due to either internal or external factors. Therefore, such PV module is disconnected, and the systems must be adjusted to the new operation state. Since the remaining converters have to regulate the bus voltage, the control must modify and adjust the reference voltages for each one of the remaining converters.

The second case is characterized by a failure where a PV module is disabled. Consequently, the remaining modules are responsible to support the bus voltage, and despite the condition in which the system is, the control parameters are adjusted.

Since there is the possibility of connecting or disconnecting PV modules, the output voltage of each converter must be adjusted according to the number of power sources connected, as shown in Table 1, because the DC bus must be regulated at a 200 V level.

3 Multi-model control strategy

System changes are inevitably due to extreme partial shading and failure problems, and a multi-model control strategy must be used. The proposed strategy provides an effective DC bus voltage regulation, and the corresponding flowchart algorithm is shown in Fig. 2. The proposed control strategy selects and adjusts the control parameters of each converter so that the voltage of the microgrid remains regulated.

The PV module detection is the first step performed by the algorithm and it is accomplished by sensing each open circuit module voltage with a resistive divider with a high ohmic value. The voltage measured provides information for evaluating if the PV module has enough solar energy or if it is damaged. Each PV module was characterized, and based on a minimum output voltage estimation that guarantees power to the lowest load considered, the algorithm detects if a PV module has enough energy. Another threshold voltage is used in the algorithm to determine if a PV module is damaged, in which case, the bypass diode failure generates a low output voltage [27].

The second step determines whether to connect or disconnect certain PV modules. Based on the first step, the decision is taken depending on whether the voltage is high enough, which means that the PV module will deliver energy without stressing it. The consideration is based on the manufacturer datasheet and the previous PV module characterization performed.

The next step consists in determining the control parameters. Regardless of the number of PV modules connected, the control must ensure that the bus voltage is located at the desired level. All the information of different models is stored in a pre-set parameters bank. Once the number of connected modules is known, the required parameters are selected for each converter.

The last step is to send the selected parameters to adjust the voltage reference point of each converter. Thus, each converter is responsible for providing a voltage level in order to keep the DC voltage energized. Under normal operating conditions, the power demanded by the loads is distributed among the connected modules. When partial shading occurs in a module, the unaffected modules have to compensate the power demand. If a module cannot provide enough power, it is disconnected in the following “PV modules detection”.

3.1 Multi-model control

The system has the ability to change the number of connected PV modules, which means that more DC-DC converters have to interact in the DISO connection. Since system complexity increases with each module addition, a modelling and control problem has to be faced. The system has to operate robustly over a wide range of operating conditions, and a simplest way to confront it is to decompose them into a simpler modelling and control problem. This approach is increasingly popular because it is based on the “divide and conquer” strategy. In this context, a multi-model control can provide such appeal. In a multi-model control, several models and/or controllers are specified a priori [28]. The do-case diagram, which is shown in Fig. 3, works as system linker between the “PV module decision” and the “parameters adjustment” where the multi-model control is allocated.

The multi-model control herein proposed works by switching the control input based on tuned models chosen for different points of operation. This allows better control of non-linear systems by limiting multiple models for the entire operating range. The multi-model control block diagram considered is shown in Fig. 4, where sp is the set point, e is the error, u is the controller output signal, d is the unmeasured disturbances, U is the input of the process, and y is the output. The model identifier α is selected by electrical characteristics of the system, such as voltage, current and power. The model parameter β is determined by the model identifier, and is based on predetermined parameters for the system. The controller setting block is used to adjust the reference point and the controller for each corresponding model. Ns is the secondary transformer turns.

3.2 Converter model

The flyback converter is illustrated in Fig. 5, where Np, Ns are the primary and secondary transformer turns; Lp, Ls are the primary and secondary inductance; RL is the parasitic series resistance of the inductor; RC is the parasitic resistance of the output capacitor; R is the output load; CC is the output capacitor; Vin is the input voltage; Vout is the output voltage.

The dynamic behavior of each flyback converter can be described by (1) [29]:

where \(\hat{V}_{\text{o}}\) is the output voltage; \(\hat{d}(s)\) is the control signal; sz1 and sz2 are system zeros; Q is the quality factor; wo is the cutoff frequency; Gdo is the gain transfer function. They are shown as (2)–(6), respectively.

In (3)–(6), D is the duty cycle; Re is defined as follows:

N is the transformation ratio:

3.3 Control scheme

With the transfer function (1), the open loop response for each output voltage listed in Table 1 was plotted and shown in Fig. 6. For all the cases a phase margin lower than 30° was observed, which indicates that the system needs to be compensated to avoid instability.

Since the system does not meet the minimum conditions of stability, a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller is used to increase the phase margins between 30° and 60° to ensure closed loop stability, and to provide a robust performance in a wide range of operation conditions.

The time-domain PID control equation is defined by:

where u(t) is the output control signal; e(t) is the control error; Kp is a proportional gain; τ is a variable of integration; Ti is the integral time; Td is the derivative time; ėf(t) is a control filter error.

The discrete PID control equation is defined by:

where tk is the instantaneous or present time; tk-1 is the previous time before present time; r is the set point value; y is the feedback output bus voltage; I is the sum of errors to the present time; Ki is an integral gain; Kd is a derivative gain.

The controller was tuned for each output voltage, and the model gain values are obtained based on a Ziegler–Nichols tuning method. The corresponding values are shown in Table 2.

Once the compensator is designed, the closed loop step response of each output voltage is analyzed. The dynamic response for each output is shown in Figs. 7, 8 and 9. The overshoot is reduced to a minimum value, which guarantees a lower number of oscillations with lower probability of instability in the bus voltage. The response time was considered to be less than 10 ms, and with the controller designed, the value is achieved. DC microgrids are slow dynamic systems since electronic loads with capacitors at their inputs are interconnected to the bus. Each converter is able to adjust its output voltage to regulate the DC bus voltage to 200 V.

4 Experimental results

An experimental prototype was built to evaluate the proposed multi-model control strategy, which consists of 4 DC-DC converters and a digital control module. Each converter has 2 optocouplers, one at the input and the other at the output, by which the sensed voltage is sent to the master control.

The main features of the system are shown in Table 3, where ΔVbus is the DC bus voltage ripple and Pbus is the power of DC bus.

Table 4 shows the specifications of each converter, where Vin is the input voltage; Iin,max is the maximum input current; Vo,max is the maximum output voltage; Po,max is the maximum power; Io is the output current; fs is the switching frequency.

Table 5 shows the operating conditions of the microgrid, where Vo,conv is the output voltage of each converter; Io,conv,max is the maximum output current per converter; Vbus is the bus voltage; Pmax is the maximum power of the microgrid bus.

The DC-DC converters and the full system were tested in order to verify the DC bus regulation under different operation conditions. The system was tested in islanding mode.

The system response was evaluated to load changes (between 25% and 70%), and the results with 4, 3, and 2 connected modules are shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12. The dynamic limitation of the converter along with the lack of transformer optimization results in that the 2-module connected case has the worst voltage overshoot and stabilization time, which are 15% and 80 ms, respectively. Compared to the theoretical closed-loop step response, it can be verified that the stabilization of the output voltage is faster when a higher number of converters are used. Thus, the fast stabilization time is observed in the 4-module connected case with 10 ms.

The system response was evaluated by changing the number of PV modules. Figure 13 shows the system response when two converters are working and a third PV module is suddenly connected. Each converter adjusts its parameters to switch from an output voltage of 100–66 V, and the bus voltage remains regulated at 200 V. Under a module connection/disconnection, the system requires 20 ms to stabilize the voltage bus, and up to ± 25% of voltage variation can be observed. The worst condition is used for the system in which there are no capacitive filters or storage elements connected to the DC bus.

Figure 14 shows the system response when four converters are working, and one PV module is suddenly disconnected. Each converter adjusts its parameters to switch from an output voltage of 50 to 66 V, and the bus voltage remains regulated at 200 V. It can be seen that the duration of the transient response is about 20 ms.

Moreover, the system response under a load and module change is evaluated. Figure 15 shows the voltage and current output of each converter when a load change, from 70% to 25%, is performed simultaneously with a module connection. It can be observed that the system goes from operating with three PV modules (66 V) to four PV modules (50 V) without affecting the 200 V DC bus level. Although a voltage variation is generated, the DC bus voltage stability is not compromised.

Figure 16 shows the voltage and current output conditions of each converter when the system goes from three PV modules to two modules operation, and a load change, from 25% to 70%, is performed. It can be noted that each output voltage of converters changes from 66 to 100 V. When a load change is done at the same time with a module disconnection, a bigger voltage variation is observed in the transient response. This case is the most critical because it involves the least amount of connected modules, when the number of modules is the highest, the voltage variation is the lowest.

One of the advantages of DISO configuration is that the efficiency of the system increases as more converters are added. Figure 17 shows the efficiency for each output voltage. For higher voltage conversion, the efficiency tends to decrease due to the losses of the converter derived from electrical stress. The control strategy herein considered allows using the largest number of enabled converters, which is reflected in a higher efficiency compared to a conventional strategy that only uses a single converter to raise the output voltage to 200 V (Fig. 17 black line).

5 Conclusion

A multi-model control strategy approach, aiming at a PV based DC microgrid, which provides a high-quality bus voltage regulation despite partial shading problems, is presented and validated by experimental results. Since each PV module has its own converter, the partial shading problem, which significantly impairs power generation in PV series arrangements, is solved by the DISO configuration. The proposed strategy solves problems such as connection/disconnection, and avoids the PV partial shade stress for extreme cases by disconnecting the affected PV module. Moreover, the control strategy, in which only 3 different models were considered, has the ability to be expanded to more models. The system was tested with load changes, showing stability and maintaining the bus voltage level. Furthermore, it was tested by connecting and disconnecting several PV modules, in which the multi-model control strategy shows an adequate response with a good result of bus voltage regulation. The proposed system is also flexible, providing modularity to connect more PV modules or arrays.

References

Kobayakawa T, Kandpal TC (2014) Photovoltaic micro-grid in a remote village in India: survey based identification of socio-economic and other characteristics affecting connectivity with micro-grid. Energy Sustain Dev 18(1):28–35

Guerrero JM, Hang L, Uceda J (2008) Control of distributed uninterruptible power supply systems. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 55(8):2845–2859

Kumar YVP, Bhimasingu R (2015) Renewable energy based microgrid system sizing and energy management for green buildings. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy 3(1):1–13

Ding G, Gao F, Zhang S et al (2014) Control of hybrid AC/DC microgrid under islanding operational conditions. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy 2(3):223–232

Yang Z, Le J, Liu K et al (2011) Preliminary study on the technical requirements of the grid-connected microgrid. In: Proceedings of 4th international conference on electric utility deregulation and restructuring and power technologies, Weihai, China, 6–9 July 2011, pp 1656–1662

Dou CX, Liu B (2013) Multi-agent based hierarchical hybrid control for smart microgrid. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 4(2):771–778

Yu X, Huang A, Burgos R et al (2013) A fully autonomous power management strategy for DC microgrid bus voltages. In: Proceedings of 28th annual IEEE applied power electronics conference and exposition (APEC), Long Beach, USA, 17–21 March 2013, pp 2876–2881

Bai J, Cao Y, Hao Y et al (2015) Characteristic output of PV systems under partial shading or mismatch conditions. Sol Energy 112:41–54

Karatepe E, Hiyama T (2010) Simple and high-efficiency photovoltaic system under non-uniform operating conditions. IET Renew Power Gen 4(4):354–368

Vemuru S, Singh P, Niamat M (2012) Analysis of photovoltaic array with reconfigurable modules under partial shading. In: Proceedings of 38th IEEE photovoltaic specialists conference, Austin, USA, 3–8 June 2012, pp 1437–1441

Bauwens P, Doutreloigne J (2014) Reducing partial shading power loss with an integrated smart bypass. Sol Energy 103:134–142

Chow CW, Belongie S, Kleissl J (2015) Cloud motion and stability estimation for intra-hour solar forecasting. Sol Energy 115:645–655

Ozdemir E, Ozdemir S, Tolbert LM (2009) Fundamental-frequency-modulated six-level diode-clamped multilevel inverter for three-phase stand-alone photovoltaic system. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 56(11):4407–4415

Peng FZ, Qian W, Cao D (2010) Recent advances in multilevel converter/inverter topologies and applications. In: Proceedings of 2010 international power electronics conference (ECCE Asia), Sapporo, Japan, 21–24 June 2010, pp 492–501

Kasper M, Ritz M, Bortis D et al (2013) PV panel-integrated high step-up high efficiency isolated GaN DC-DC boost converter. In: Proceedings of 35th telecommunication energy conference—smart power and efficiency, Hamburg, Germany, 13–17 October 2013, pp 1–7

Mäki A, Valkealahti S (2012) Power losses in long string and parallel-connected short strings of series-connected silicon-based photovoltaic modules due to partial shading conditions. IEEE Trans Energy Convers 27(1):173–183

Dhople SV, Ehlmann JL, Davoudi A et al (2010) Multiple-input boost converter to minimize power losses due to partial shading in photovoltaic modules. In: Proceedings of 2010 IEEE energy conversion congress and exposition (ECCE), Atlanta, USA, 12–16 September 2010, pp 2633–2636

Siri K, Willhoff M, Hu H et al (2009) High-voltage-input, low-voltage-output, series-connected converters with uniform voltage distribution. In: Proceedings of 2009 IEEE aerospace conference, Big Sky, USA, 7–14 March 2009, pp 541–547

Siri K, Willhoff M, Truong C et al (2006) Uniform voltage distribution control for series-input parallel-output connected converters. In: Proceedings of 2006 IEEE aerospace conference, Big Sky, USA, 4–11 March 2006, 12 pp

Siri K (2014) System maximum power tracking among distributed power sources. In: Proceedings of 2014 IEEE aerospace conference, Big Sky, USA, 1–8 March 2014, pp 1–15

Qu L, Zhang D, Bao Z (2017) Output current-differential control scheme for input-series-output-parallel-connected modular DC-DC converters. IEEE Trans Power Electron 32(7):5699–5711

Augustine S, Lakshminarasamma N, Mishra MK (2016) Control of photovoltaic-based low-voltage DC microgrid system for power sharing with modified droop algorithm. IET Power Electron 9(6):1132–1143

Tenti P, Caldognetto T, Costabeber A et al (2013) Microgrids operation based on master-slave cooperative control. In: Proceedings of 39th annual conference of the IEEE industrial electronics society (IECON), Vienna, Austria, 10–13 November 2013, 8 pp

Etemadi AH, Davison EJ, Iravani R (2014) A generalized decentralized robust control of islanded microgrids. IEEE Trans Power Syst 29(6):3102–3113

Li Y, Nejabatkhah F (2014) Overview of control, integration and energy management of microgrids. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy 2(3):212–222

Wang Y, Lin X, Kim Y et al (2014) Architecture and control algorithms for combating partial shading in photovoltaic systems. IEEE Trans Comput Des Integr Circuits Syst 33(6):917–930

Deng S, Zhang Z, Ju C et al (2017) Research on hot spot risk for high-efficiency solar module. Energy Proc 130:77–86

Böling JM, Seborg DE, Hespanha JP (2005) Multi-model control of a simulated pH neutralization process. IFAC Proc Vol 38(1):591–596

Middlebrook RD, Slobodan C (1976) A general unified approach to modelling switching-converter power stages. In: Proceedings of 1976 IEEE power electronics specialists conference, Cleveland, USA, 8–10 June 1976, pp 521–550

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

CrossCheck date: 20 September 2018

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

CORREA-BETANZO, C., CALLEJA, H., AGUILAR, C. et al. Photovoltaic-based DC microgrid with partial shading and fault tolerance. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 7, 340–349 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-018-0477-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-018-0477-2